International Lives and National Biographies: Visualisation Against the Grain

Reusing and transforming data from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography to enrich our understanding not of the British nation per se but of the rich, varied, and changing forms of British-Isles internationalism from the 11th-century to the present.

Project Leader: Christopher Warren

Design Researchers: Michele Mauri, Daniele Ciminieri

Scholar: Meliha Handzic

About the project

National biographical dictionaries like the Dictionary of National Biography, conceived originally in the late nineteenth century, might seem to some as inescapably bound to the nationalist projects of their era and thus of little use for reconstructing the international republic of letters. But recent digital editions and updates, like that of the monumental Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), offer compelling opportunities to mine and visualise large quantities of historical data, often in ways quite at odds with nineteenth-century nationalist historiographical aims.

Aim of the project

What can the nearly 60,000 lives documented in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) tell us -in aggregate and individually- about the development and character of internationalism over time?

Case study

In this project, we reuse and transform data from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography to enrich our understanding not of the British nation per se but of the rich, varied, and changing forms of British-Isles internationalism from the 11th-century to the present. In so doing, we contextualize the international republic of letters within a broader framework of internationalisms that includes exploration, military campaigns, evangelism, connoisseurship, and the construction of empire.

Design Process

Our starting point was a single 652 MB file containing roughly 62 million words of the ODNB richly marked-up in SGML. Christopher Warren and Carnegie Mellon University colleagues Max G’Sell, Jessica Otis, Scott Weingart, and Matthew Milideo had earlier extracted some structured data and metadata from the ODNB using the custom-built Python scripts in tandem with the Python library BeautifulSoup. In addition to unique identifiers, names, life dates, and historical significance for each individual, each row in our initial spreadsheets contained a count of unique foreign place names mentioned in each biographical entry, a measure that would become important as we addressed the issue of identifying ODNB figures of particular international interest in such a large corpus. It was possible to extract such numbers thanks to a useful tag in the ODNB, <b bi=”n”>, which flagged all locations outside of the British Isles. Hypothesizing that the “density” of foreign places in an entry could help identify the ODNB’s most international figures, we tested several rough and ready numerical metrics of internationalism grounded in the number of foreign place names with respect to the total length of the article and settled on weighting coefficients based on the diversity of and accuracy of the results. Subsequent exploratory visualizations helped us understand key aspects of the data, including the proportions per century of strictly local lives (those in which no foreign locales are mentioned) to those that included more international locations.

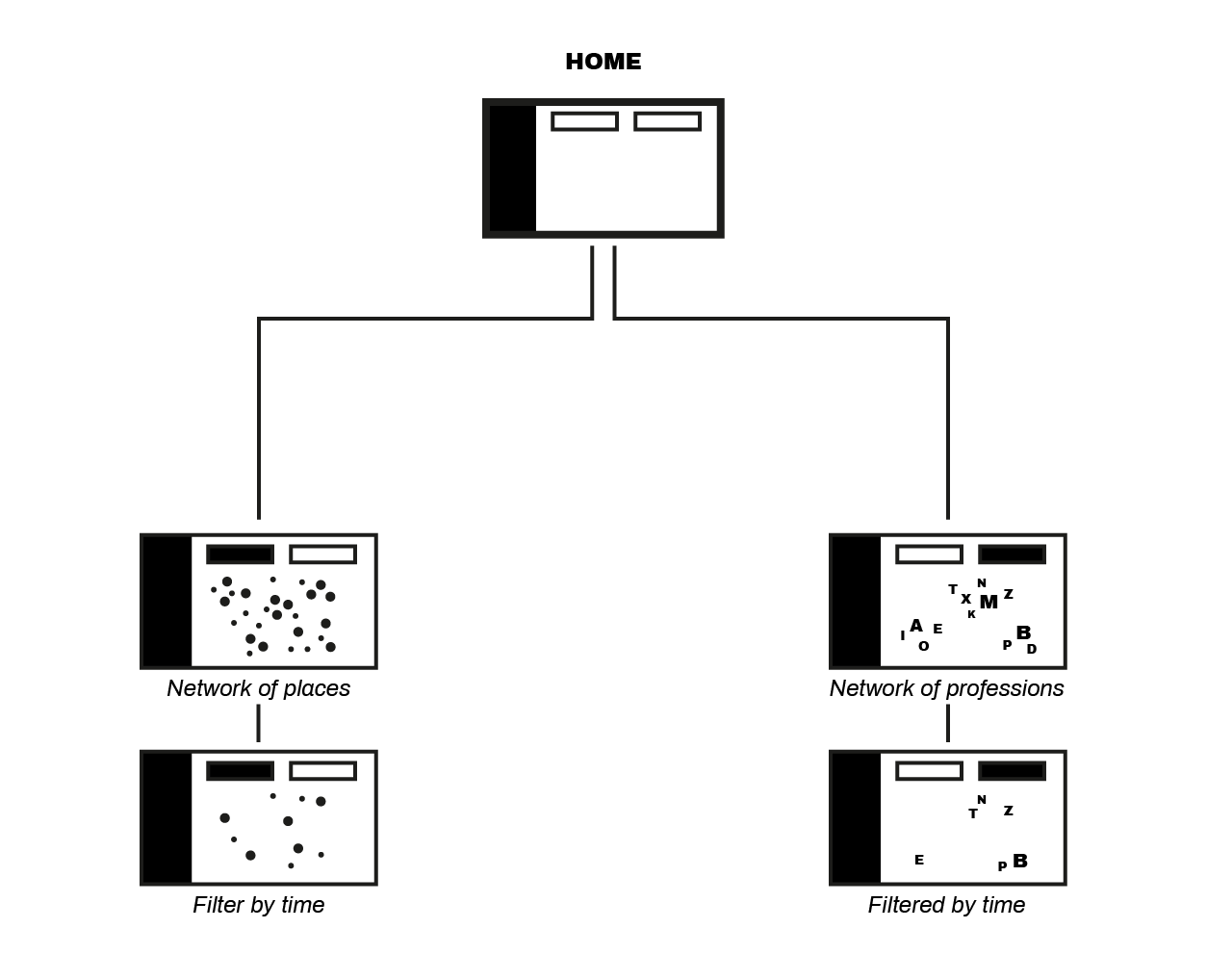

Project Diagram

Conclusions

Findings

While our work in this weeklong workshop was necessarily brief, it yielded three preliminary findings.

Firstly, highly speculative accounts of globalization notwithstanding, scholars have rarely inquired about, much less answered, the question of how elites’ patterns of locality and internationalism have changed over the longue durée. Our work has identified a broad pattern of rising internationalism in elite British lives, but one in which the seventeenth century represents a surprising anomaly. The proportion of biographies that mention foreign places actually falls to a local low in the seventeenth century (57%), followed by a sharp rise toward the nineteenth century peak of 84%. Some potential reasons include, on the one hand, the Civil Wars in the British Isles and, on the other, the Thirty Years’ War on the continent. The combination, we speculate, gave many seventeenth century British lives a deeply local character, one perhaps amplified by historians’ tendencies to mention locations of battles and troop movements in seventeenth-century biographies.

A second finding concerns the occupations of those broadly understood as “international figures” in the early modern period. With some exceptions, the early modern individuals who emerged as their period’s topmost international figures were less members of the international republic of letters than they were travelers, explorers, military officers, and, of course, royals. Such context helps us see those Britons who did participate in the Republic of Letters as participating in a distinct and perhaps counter-cultural version of elite internationalism, one interestingly set apart from the dominant forms of internationalism of the day.

Our third major finding, relevant particularly as scholars work increasingly with larger biographical corpora, concerns the role of historians and historiographical conventions in determining current perceptions of internationality. Regarding the outsized role of exploration and military affairs vis a vis the Republic of Letters in our findings, some selective comparisons of individual biographies have suggested that what we’re capturing has much to do with historiographical conventions, such as military historians’ proclivities for listing places in military campaigns as opposed to, say, intellectual historians’ privileging of names and ideas at the possible expense of places.

A second note concerning historiography is this: among several possible variables that we considered, the variable that correlated most highly with the number of unique foreign places mentioned was the total length of the biography. This to a certain extent is unsurprising (the more space devoted, the more room to mention foreign locales), and yet the finding remains important to emphasize lest scholars uncritically reproduce predecessors’ judgements that determined biography lengths in the first place by failing to consider word count. In ranked order, the features of a biography that correlated most highly with number of unique foreign places was biography length, total number of unique names in an entry, number of unique local place names, marital status, and finally gender. There was a very slight negative correlation between whether a subject’s entry included baptism data, on the one hand, and the number of foreign places mentioned on the other.

There are of course some a few more caveats and challenges to note. Initially, we found it difficult to successfully conceptualize large-scale visualizations of nearly 60,000 data points. It turned out that detailed, collaborative attention to particular data points and conceptual issues was necessary before we could produce communicative large-scale visualizations. Lastly, the ODNB data is exceptionally well marked-up, but across 60,000 entries there are of course some inconsistencies that introduce occasional errors and misimpressions. Further data cleaning, as ever, would likely produce slightly different results and reduce misleading visualizations.

Conclusions & Further Research

At the broadest level, our visualizations exemplify how we might study and visualize nineteenth-century biographical dictionaries against their nationalist grain. In so doing, we also address imminent challenges associated with exploring and analyzing the broadest currents of large-scale prosopographical data.

In the end, different types of visualizations catalyzed different stages in the research: initial Excel bar charts helped us explore distributions of local and international figures over time; pen and paper sketches opened a process of imagining alternative ways of understanding relationships among people, places, and professions; and highly expressive overview visualisations informed our perceptions of working with international biographies against the backdrop of a much larger corpus that could ultimately be sorted and visualized according to any number of further research questions.

The dynamic prototype that was our final product facilitates research on:

-

the dynamic geographies of internationalism from the 11th-century to the present

- individual lives in relation to places mentioned in their biographies

- intersections among international places and historical occupations and professions

Further research could take many different directions, but some especially promising avenues we have identified include further work on the historiographical conventions around figures associated with the international republic of letters in order to gain better perspective on their distinctive characteristics and distinctiveness vis a vis one another. This in turn would focus attention on slightly different slices of the ODNB data, sets that could be studied according to refined measures dedicated to new questions. We see special potential in topical analysis of ODNB entries as a way not only of accessing alternative versions of internationalism not captured by the raw counts of foreign places names but also for identifying and studying a wide range of other interesting questions.

Ultimately, because national biographical dictionaries like the ODNB are so large, it has been difficult in the past to see them as more than mere vessels of the individual biographies contained therein. However, visualization offers digital humanists valuable opportunities to train their “macroscope” on large-scale corpora–to treat projects like the ODNB as interesting objects of study in their own right, objects whose distinctive features and topographies might in future research even be compared and combined. [1]

References

[1] Graham, Shawn, Ian Milligan, and Scott Weingart. Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope. Imperial College Press, 2015.