Correspondences over itineraries

Strategies for superimposing the correspondence of a given individual on top of the physical itinerary of that individual.

Project Leader: Vladimir Urbanek

Design Researchers: Beatrice Gobbo, Alex Piacentini

Scholars: Roberto Evangelista, Magnus Ulrich Ferber, Vladimir Urbanek

About the project

Visualisations merely displaying the places to and from which letters were sent cannot make sense of the correspondences of itinerant individuals.

In response to this challenge, this group has explored strategies for superimposing the correspondence of a given individual on top of the physical itinerary of that individual. The career of the Czech educational reformer and pansophist Jan Amos Comenius (1592–1670) provides an ideal test case: during a long lifetime, he moved frequently and very widely throughout south-eastern, central, northern and north-western Europe, staying for longer periods especially in the Bohemian Lands, German territories of the Holy Roman Empire, Greater Poland, England, Royal Prussia, Hungary and the Netherlands.

His correspondence covers approximately the same geographical territory and includes not only important western centres of scholarship such as Amsterdam, London and Paris, but also cities and towns on the margins of the Republic of Letters but with lively intellectual traditions, often affected by the Thirty Years War and the First Northern War, such as Leszno, Gdańsk, Elbing and Brzeg. The group has aimed at finding a digital tool for visualisation of the geographical scope of Comenius’s correspondence and his location history and at developing a polished solution of the task to represent visually both correspondence and itinerary data sets.

Aim of the project

The principal aim of this project was to address the following questions:

-

What is the best solution which would enable to combine metadata largely derived from Comenius’s catalogue in the EMLO with data on his location history in order to visualise changes in Comenius’s correspondence contacts / network in relationship to his movements during his whole life?

-

Are these changes (in geographical scope and prosopographical composition) closely related to person’s physical movements or rather independent on them?

-

To what extent can we use an individual pattern as a model for representing movements and changing patterns of scholarly correspondence networks in a more general way, for example in the periods of wars, displacements and exile, such as the Thirty Years War?

-

Would it be possible to find a solution which may be reusable for other itinerant scholars and their correspondence networks, both in periods of relative peace (Erasmus or Leibniz) and in the periods of wars (John Dury)?

Case study

The members of the group acquainted themselves with Jan Amos Comenius (1592-1670) as a very suitable test case for studying strategies for superimposing the correspondence of a given individual on top of the physical itinerary of that individual. Metadata of Comenius’s correspondence which include ca 560 letters sent and received were derived from the Comenius catalogue within the Early Modern Letters Online (EMLO) but some important corrections were made in this dataset in order to specify for example incomplete, ambiguous and unclear dating of the letters.

These corrections were largely based on the current work in progress of the Department of Comenius Studies and Early Modern Intellectual History at the Institute of Philosophy, Czech Academy of Sciences, preparing the first volume of the critical edition of Comenius’s correspondence. Data for Comenius’s physical movements were provided by the same Comenius team from Prague.

In addition to Comenius’s biography and its relationship to the general questions of communication within the European Republic of Letters in the periods of wars and displacement, the nature and format of the datasets were discussed by the members of the group. Some of the research questions, their spatial and temporal aspects and a principal aim of the project were discussed (see above) and a target group of potential users of the visualisation tool was specified.

Design process

The crucial methodological problem lay in finding the way how to use structured metadata and data in the MS Excel tables in order to create a functional visualisation tool able to address research questions. Before the beginning of the group’s work, the Comenius team (Iva Lelková and Vladimír Urbánek) at the Institute of Philosophy, Czech Academy of Sciences produced several visualisations of Comenius’s correspondence using Palladio.

It was important that the scholars and designers involved in the group agreed that Palladio is not sufficient for solving research questions, therefore there was a need to find a more flexible tool which would enable more detailed and analytical perspective. The scholars focused on solving problems related to incomplete or uncertain data within the dataset in order to use them in the best possible way for visualisation and for addressing research problems.

The designers suggested various visualisation models suitable for the tasks. The group members discussed these models together and made decision about a solution. Despite the fact that the group members had no previous experience with the Design Sprint format, the cooperation proved to be very fruitful.

The group’s work was divided into five days and five steps devoted to:

- Sketching and proposing various models of solution

- Work with two metadata sets and refining the chosen model

- Implementing the data and creating the prototype

- Work on a refined prototype and architecture of the tool’s interface

Sketching and proposing various models of solution

In the second step the members of the group devoted considerable time to brainstorming and sketching competing (and in some cases complementary) models of visualisation. These models were basically three:

- Model using the principle of “time split” or time split model

- Matrix-map model or a analytical model

In the next days one more model appeared based on the idea of concentric circles representing time, space and prosopography related to Comenius’s correspondence and his itinerary.

There was not enough time, however, to develop this model further and it was decided to leave it as a potential new visualisation to experiment with in the future. Advantages and disadvantages of the respective models were carefully thought through. The narrative model based on six chapters / six maps of Comenius’s life seemed to be very appropriate for educational purposes but limited in its viability for other case studies.

The time split model proved to be promising for experimenting with a timeline (e.g. focusing on changes in correspondence in relationship with specific historical or biographical events) but less so in its suitability to show a overall picture. Finally, the matrix-map model appeared to be useful for research purposes and flexible enough to be reused in other case studies.

Work with two metadata sets and refining the chosen model

In the next step the group decided to choose the matrix-map model and develop it further. Since the dataset of Comenius’s location history appeared to lack the structural consistency needed for the visualisation it was necessary to simplify/standardize the format of the data and to add information regarding “long” stays and “short” journeys which would be represented in the graph and map by thick and thin lines.

It was also necessary to solve as many of uncertain or incomplete information about dates and places as possible in order to have a reasonable visual result. During the clearing of the datasets and refining of the chosen model it turned out that it would be difficult to deal with more than 100 geographical names on the vertical axe of the matrix and this remained to be a considerable challenge until the end of the project. The group also faced problems related especially to uncertain dates of some letters and unclear chronology of some of Comenius’s journeys.

This was a big challenge, and in some cases the visual approach, and the previous setting of metadata, helped us to formulate plausible hypothesis, e.g. about the chronological order of visited cities. In this phase of the project the first schematic versions of the prototype were created (Figs. 1-3) which, however, did not use real data.

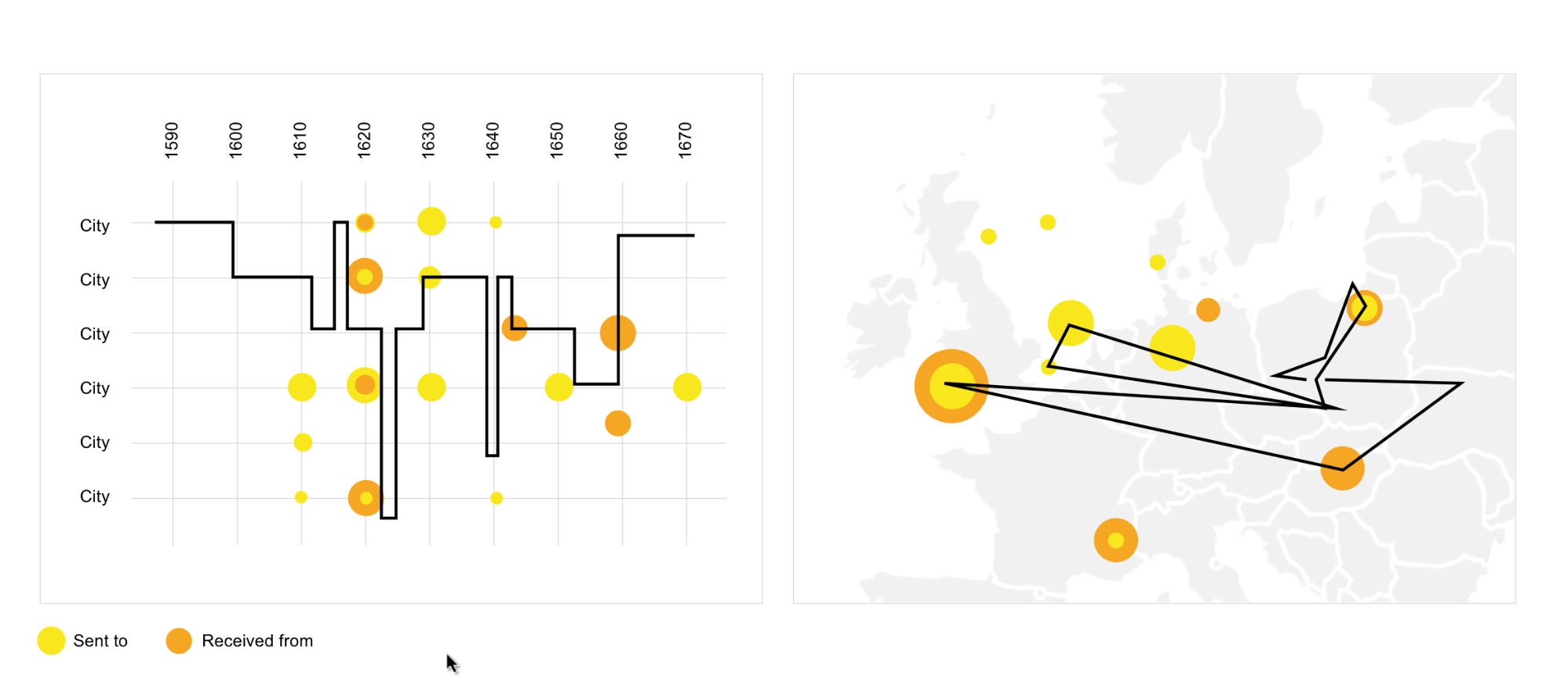

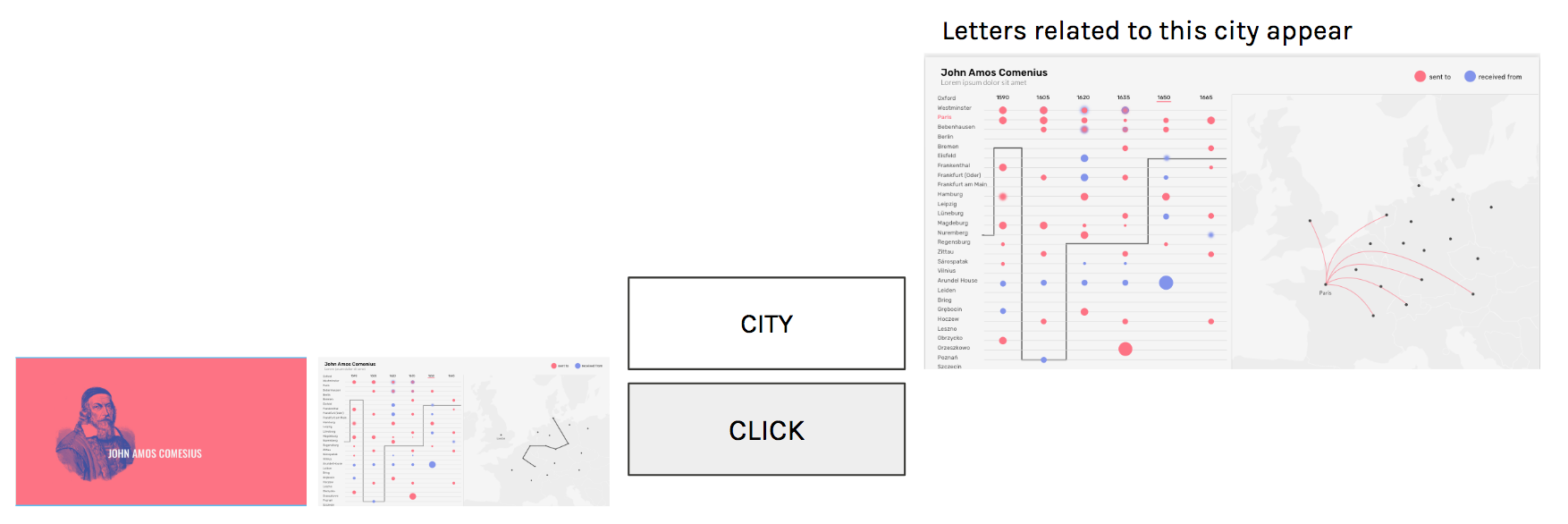

Fig. 1: The figure 1 represents one of the first sketches of the matrix-map visualisation. The matrix with two axes enables to follow both temporal and geographical aspects of Comenius’s location history and his correspondence in a form of a “snake”. The cartographical representation on the right shows the paths of his journey and stays and those of his sent and received letters. Matrix and map are intended to be interactive, so a user may choose just a part of Comenius’s location history or a time period and see an appropriate cartographical representation on the map.

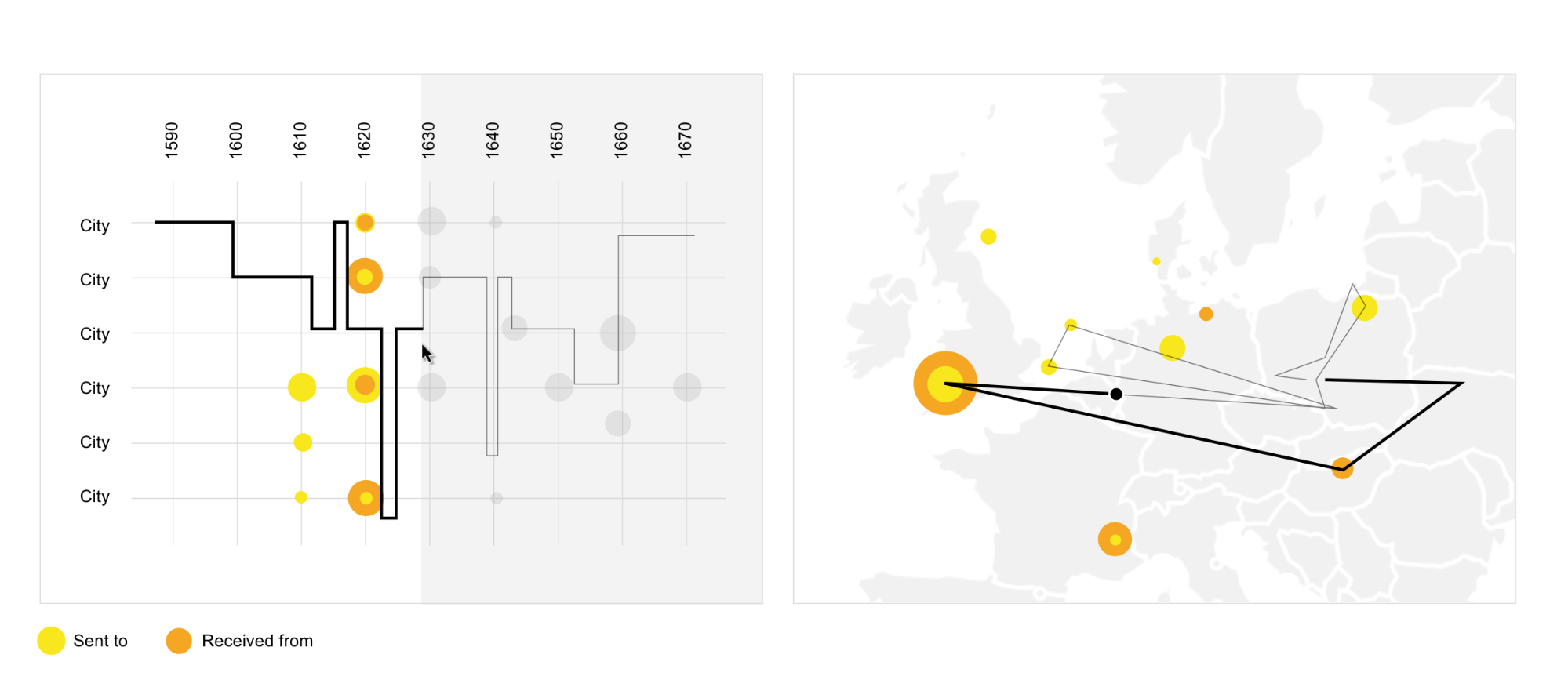

Fig. 2: This figure shows the matrix-map interaction by choosing a particular period of Comenius life. The black line in the matrix represents the time spent by Comenius in each city and the travel distances on the map. The coloured points represent the amount of received and written letters.

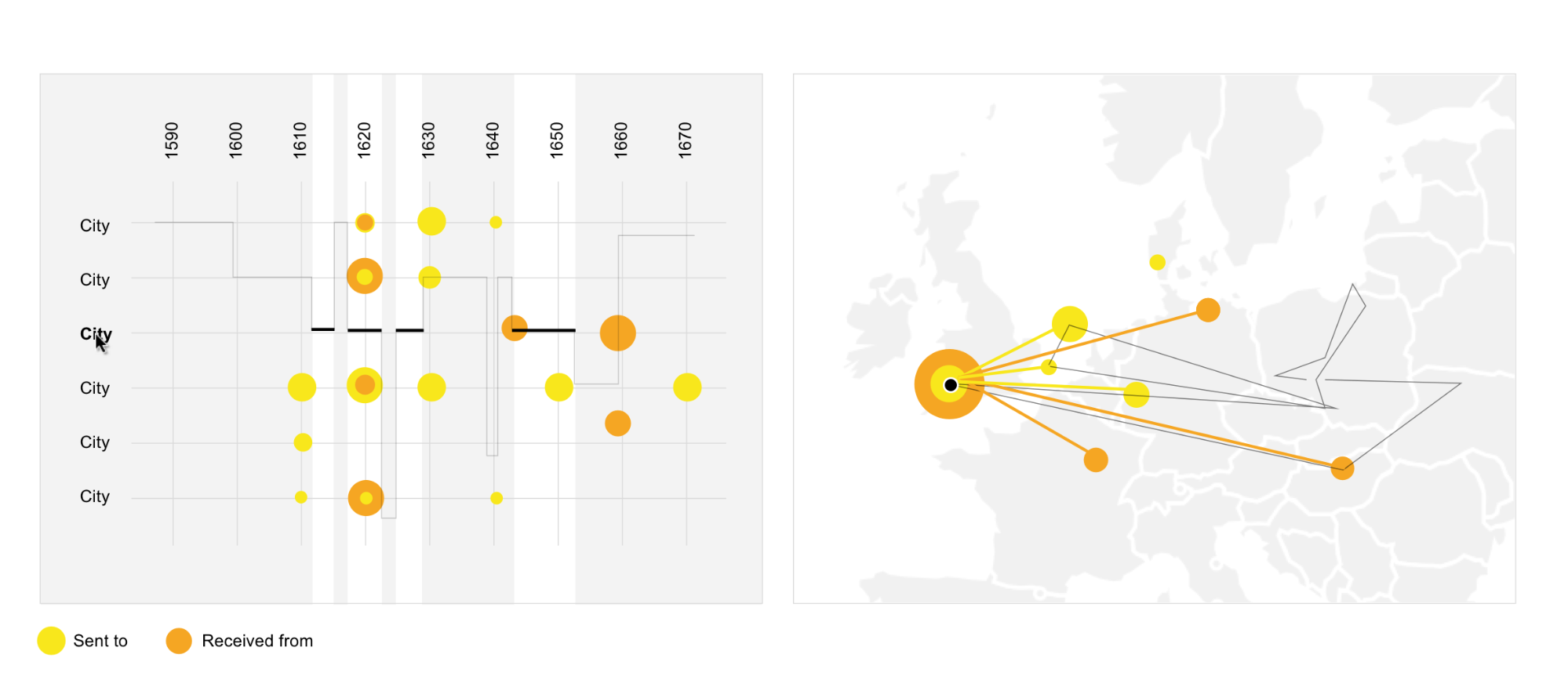

Fig. 3: When selecting a city on the matrix, the map highlights that city, plus particular cities and towns which Comenius corresponded with (from and to).

Implementing the data and creating the prototype

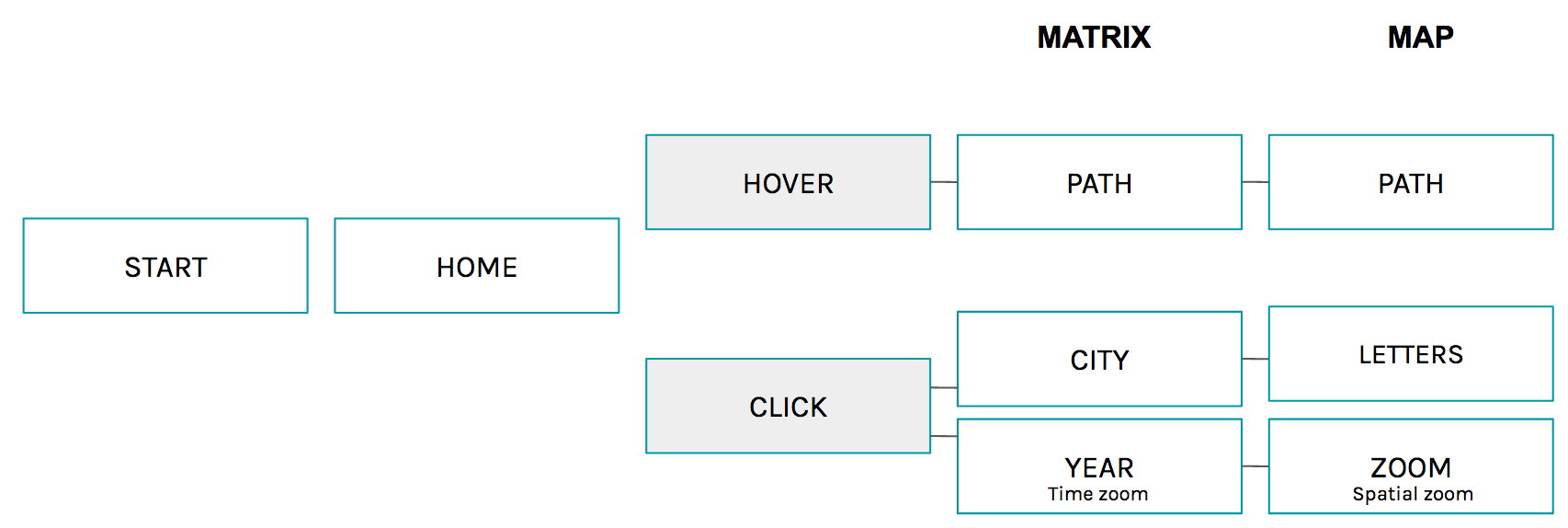

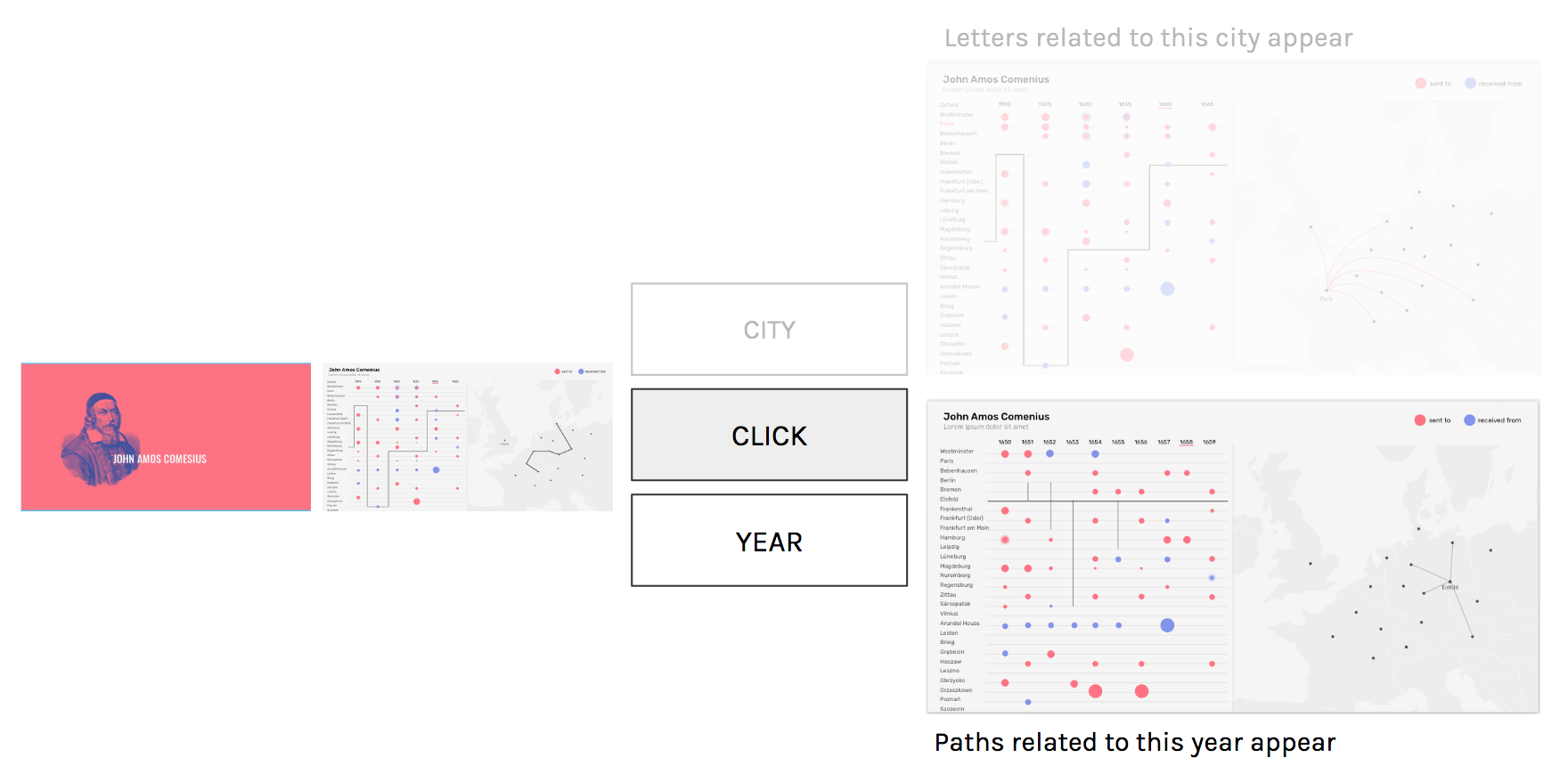

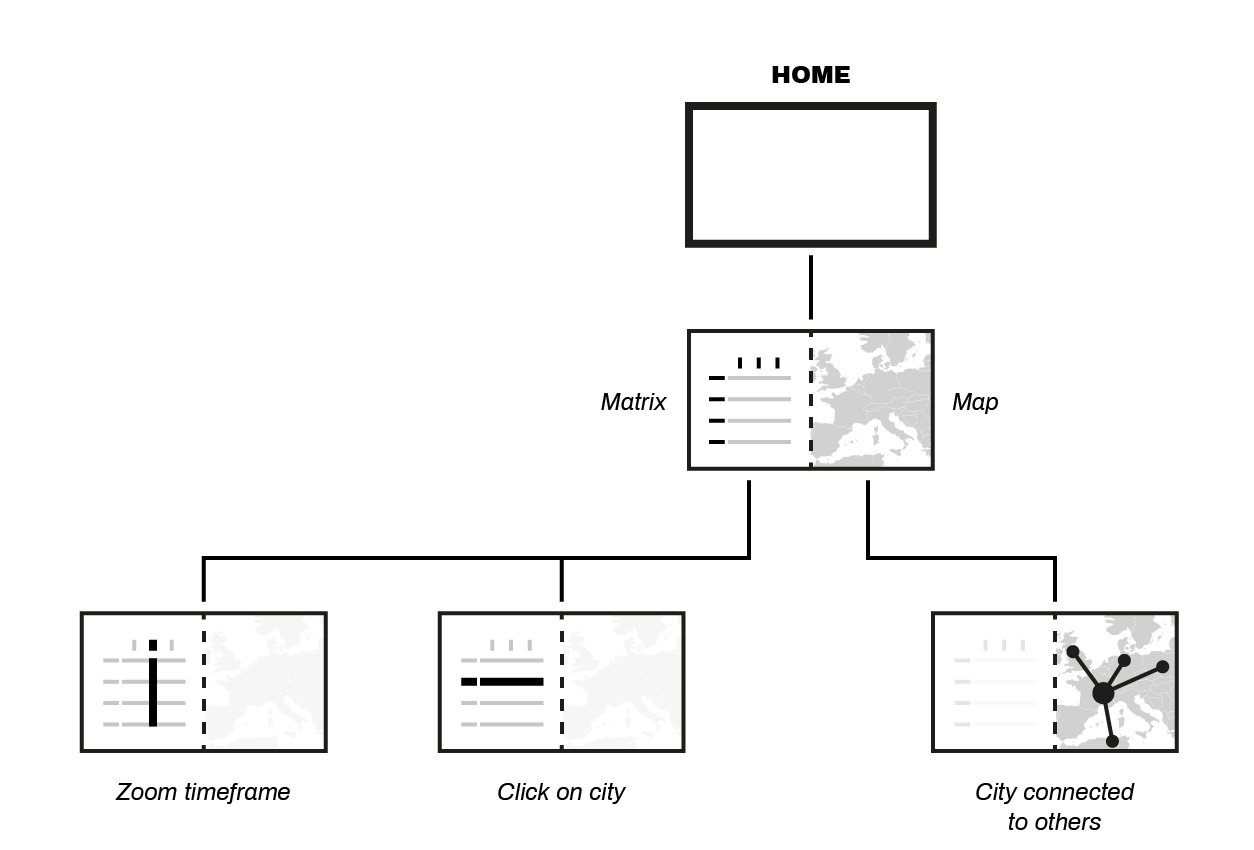

The fourth step consisted in the implementation of the data of Comenius’s location history to the framework React. The members of the group explored the possibilities to zoom on specific time periods or individual cities in the matrix. These functions of the tool were incorporated to the tool’s interface architecture (Figs. 4-6).

Fig. 4: This figure represents the tool’s interface architecture.

Fig. 5: Zoom on a single city shows both letters sent from and received in this city (this visualisation does not use real data).

Fig. 6: Zoom on one year shows journeys made in this particular time frame (this visualisation does not use real data).

Work on a refined prototype and architecture of the tool’s interface

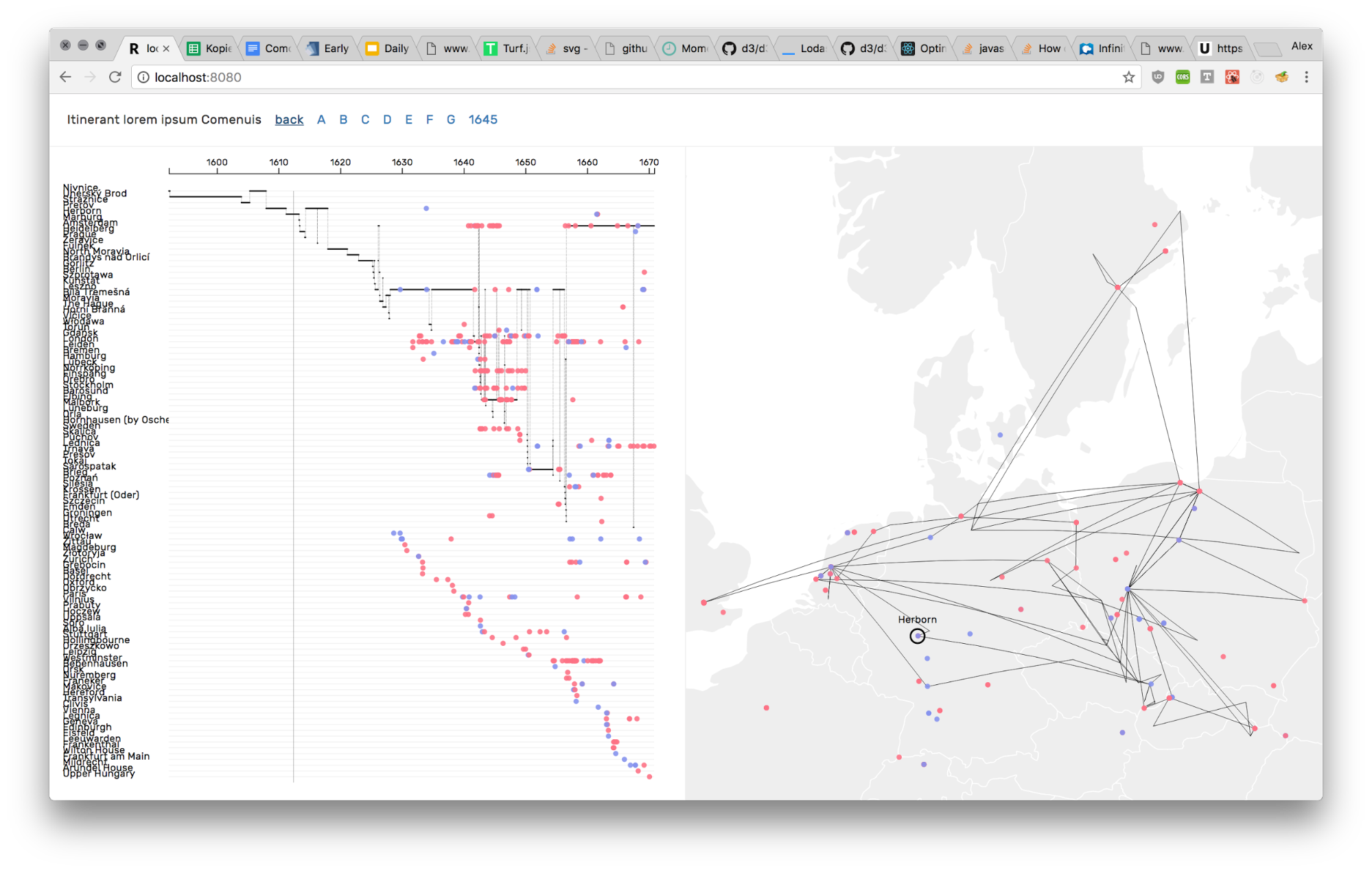

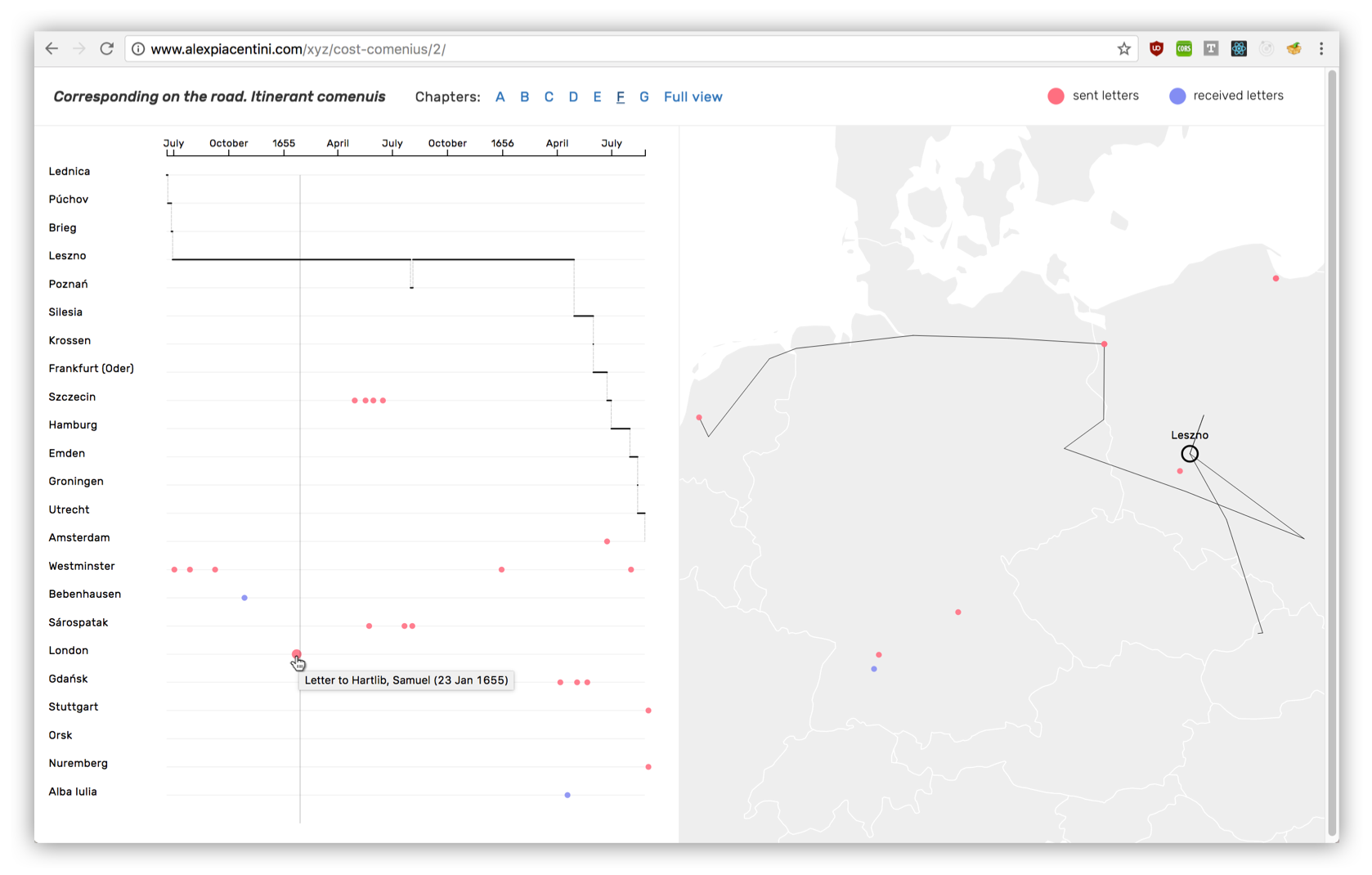

In the last step a refined prototype was developed which incorporated both data for the itinerary and for the correspondence (Fig. 7). The itinerary is represented in a matrix with two axes with the horizontal line for time, and the vertical one for places.

Within this diagram the stays and the movements of Comenius are shown as a “snake”. This visualisation is interconnected with a map where the “real” geographical locations are represented. In the same matrix all letters are located as points (red points for sent letters, blue for received ones) with their times and places, which are also fixed in the map. Possibilities to choose a period of time or a specific city are established for a user who can also use one of the seven possibilities (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) to zoom on a shorter period of time and an appropriate cartographic representation.

Fig. 7: This figure represents a refined matrix-map prototype.

Project Diagram

Conclusions

Findings

One of the most promising features of the refined prototype is that it enables to represent in a considerable detail how one person’s physical movements are related to changing patterns of his/her correspondent contacts.

So for example in Comenius’s case, there is an active phase in the development of his correspondence contacts with Hartlib and some of his key correspondents, such as Joachim Hübner and Johann Moriaen, which not only includes intensive discussions of Comenius’s pansophic project but also prepares his journey to London in 1641. His itinerary after leaving England reflects to considerable extent previously established correspondence contacts with figures like Moriaen or Hotton in Amsterdam but also an interest in his work of figures with whom he never corresponded (like Descartes) sparked by intermediary figures with whom he did correspond but whom he never met (like Mersenne). At the same time, however, his itinerary in the 1640s reflects development of new correspondence contacts with Sweden, the Netherlands and Baltic area (e.g. Gdańsk/Danzig).

Our prototype can also help formulate questions regarding frequency of correspondence contacts in certain period in relationship to a region or city Comenius was and its “accessibility”/connectedness. Of course, we have to keep in mind that we are working only with extant letters and that this is only a part of an actual correspondence exchange. It is striking, therefore, that the correspondence contacts with Hartlib and figures central to his network were certainly more frequent in the 1630s and early 1640s, even if we know only a small portion of them and even if the correspondence connection between Leszno and London was not that easy as from Gdańsk or Elbing. After moving to Elbing in 1642, the correspondence with Hartlib was less frequent (which may be convincingly documented not only by the number of extant letters but also by complains in the letters of John Dury) even if the postal connection between Elbing and London was obviously better.

Despite the fact that the overall visualisation of Comenius’s correspondence and his movements in a single matrix-map tool may seem overloaded, zooming on shorter periods (Fig. 8) of time and/or on individual cities and the further elaboration of the tool architecture may help interrogate data on smaller scale.

Fig. 8: The visualization with a zoom on a certain time frame.

Conclusion and further research

-

The matrix-map tool is a useful aid which may help produce new research questions and verify some hypotheses but it certainly needs further refinement and development.

We should develop the function of drilling-down from the matrix-map to another view that shows more details of the letters and correspondents related to certain cities and shorter period of time in relationship with the cartographic representation of Comenius’s movements and letter exchange in the given period.

Navigation could loosely follow this principle: Matrix (when?) > Map (where?) > New view (who?)

This function may for example be used to investigate in detail intensive correspondence between Amsterdam and London in the first years after Comenius’s arrival to Amsterdam in 1656 in comparison with his declining epistolographic contacts which survived from the previous periods / stays / journeys in Poland and Hungary.

-

The matrix view could be improved adopting some sort of grouping by country to show a more overall picture in the beginning, and only expose all the detail once user navigates in time/space.

-

We should further develop the timeline on the matrix-map model which would enable us to include important dates / events in European and local history which would help users (especially students) understand relationship between these events (such as the defeat of Bohemian Revolt in 1620, an expulsion of Protestants from the Bohemian Lands in 1628, the beginning of the English Revolution in 1641-42, the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Northern War between Poland and Sweden) and Comenius’s itinerary / development of his correspondence contacts.

-

The matrix-map tool should be tested on other datasets of the itinerant scholars in the period of the Thirty Years War whose correspondence and location history intersected with that of Comenius, such as John Dury.

-

The suitability of a circle model (concentric circles) should be further tested.

-

Funding for further refinement and development will be sought within the digitalization programmes of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

-

The design-sprint format proved to be very fruitful and inspirational. Perhaps some of us had feeling that one more day would help us refine our tool in a more sophisticated way.