Intersecting correspondences

Exploring techniques for visualising multiple intersecting correspondences simultaneously

Project Leader: Philip Beeley

Design researchers: Tommaso Elli, Marco Quaggiotto

Scholars: Thomas Wallnig, Mat Wilcoxson

About the project

Most visualisations of correspondence to date attempt to map or graph letters to and from a single individual. This group has broken new ground in exploring techniques for visualising multiple intersecting correspondences simultaneously - that is to say, groups of letters to and from multiple individuals who are in contact with one another and with many common correspondents as well.

Aim of the project

The aim of the group was to focus on three main tasks:

- To devise tools for visualizing large correspondence corpora in their relations to each other, using the metadata of 4-5 correspondences contained in EMLO, and to do this in a readily comprehensible way.

- To help users navigate intersections of such corpora; especially when seeking to explore new aspects of the data such as the role played by sub-networks or gain new insights into knowledge exchanged between third parties.

- To develop visualizations of a correspondence corpus that allow a better understanding of different scholarly roles: author as sender, author as recipient, and author mediator of exchanges between between third parties.

Case study

One test case has been a series of overlapping correspondences of individuals associated with the founding of the Royal Society of London either side of 1660 (Aubrey, Lister, Oldenburg, Wallis), while another test case consisted in the c. 150 Leibniz letters extracted from the Leibniz correspondence database as involving an otherwise “uninvolved third person”.

The group soon found common ground, in that the scholars sketched out the specific nature of the problems they wanted to focus on (“Aim of the project”), and the designers made suggestions as to how to use visualisation tools to address these problems. It was important that both sides of the group were aware of the precise nature of the tasks, and their relative weight in the overall structure of the design sprint. An agreement was soon reached that the complexity of the problems required three different levels of approach (see “Design Process” and “Findings”). It was helpful that some group members had had previous experience not only with the Design Sprint format, but also with its specific application in the context of COST Action IS1310. In addition, it was helpful that both among the designers/developers and the scholars a similar general approach and mindset prevailed.

Design Process

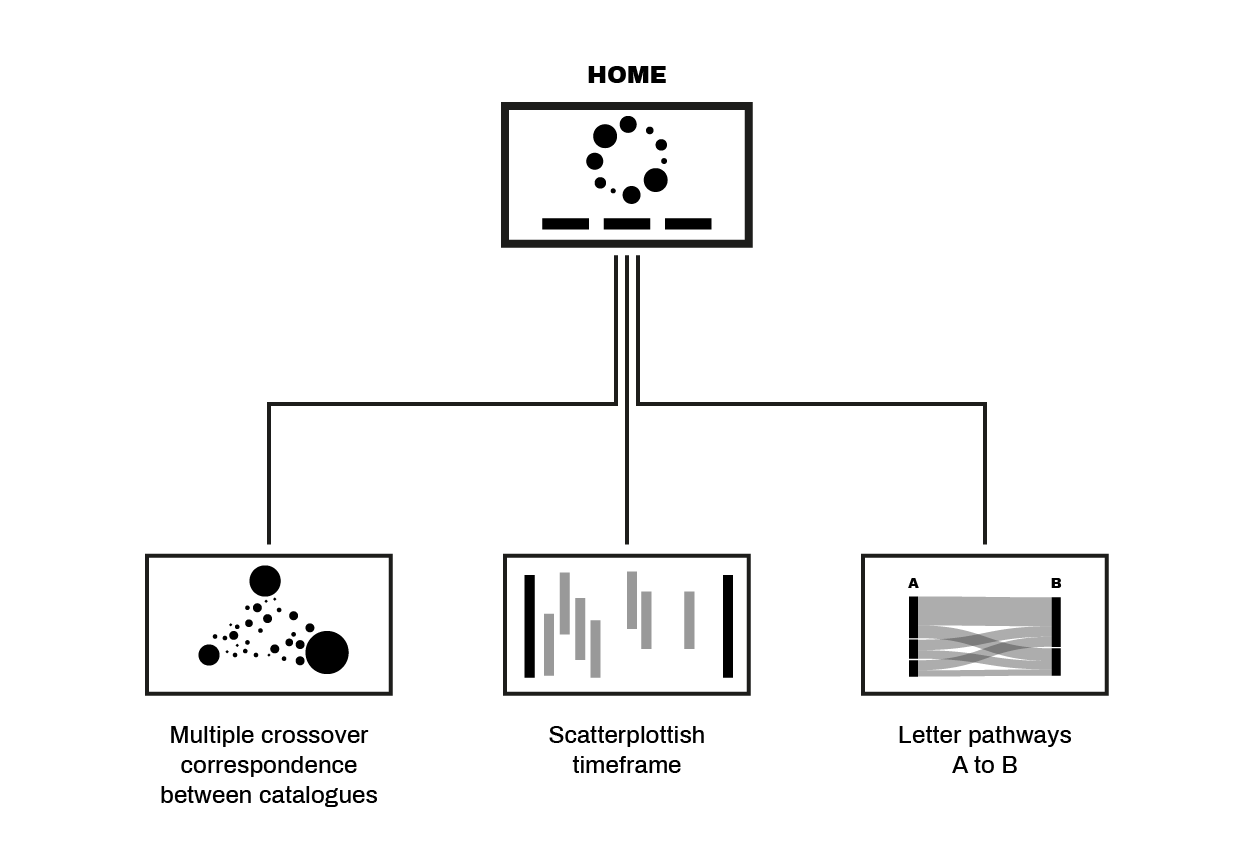

SUNBURST VIEW. It was felt that a general introductory graphic would be useful, allowing users to navigate from this to intersecting correspondences. The sunburst partition model would feature the names of catalogues (EMLO) or the names of fellows (Royal Society). This model can be enhanced with additional information (dates, memberships, country of origin, further hierarchies, and so on). The interior space can be used to advertize featured catalogues. The following presentation is based exclusively on the proposed EMLO application, but can be applied with minor changes to the study of institutional archives. - By selecting 3, 4, or 5 names from the circle one would determine the subjects of the “triangular”, “quadrangular”, or “pentagular” visualization; by selecting 2, the names would be subjects of the so-called “scatterplotish” view.

TRIANGULAR, QUADRANGULAR, or PENTANGULAR VIEW. This format is based on 3, 4 or 5 names from the sunburst view and depicts - without the dimension of time - both the entire correspondence networks and the communalities between catalogues, i.e. the persons present in more than one catalogue, distributed across the space according to the number of exchanged letters.

SCATTERPLOTISH VIEW. This view has a temporal component: it shows intersecting lives of individuals

- across their direct correspondence between A and B (thereby providing a visual reflection of the depth and intensity of the exchanges between them);

- debate - this view can be enhanced by the addition of correspondence from their respective networks sent and received by A and B at the same moment in time;

- Intersections of the networks of these two correspondents, now particularized (in contrast to the triangular visualization and its cognates). The user is informed of the persons who exchanged letters with each of the two correspondents separately and of the dates at which these exchanges took place. Such information will provide users with an initial indication of the existence of subnetworks to be explored further.

- Focusing on one single scholar, on can look at letter pathways, choosing for one specific individual the role as (1) sender (including double authorship of a letter and ghostwriting); (2) as an intermediary; and (3) as recipient of indirect correspondence. – We discarded versions that would allow for a chronological view (see “Conclusions”) of letters of indirect correspondence, and also versions that tried to deal with non-intentional correspondence (in theory, one could tackle that by using different colours in the flow diagram; however, this tends to become more of an individual transmission history). Semi-intentional passing-on of letters (e.g. Leibniz, John Locke, Lady Masham and Samuel Clarke) could be handled, for instance, by weaker colours).

The user journey starts with (SUNBURST VIEW), while views (TRIANGULAR, QUADRANGULAR, or PENTANGULAR ) and (SCATTERPLOTISH VIEW) can be accessed through embedded links from that first screen.

Project Diagram

Conclusions

Findings

A central finding concerned the fundamental structure of the interface/s: that in order not to overload a single visualisation, it is helpful to offer different views to address specific questions. Furthermore, that it is important already early on in the design stage to have crucial factors such as simplicity and ease of operation in view. The latter consideration was seen as being of great significance when seeking to create a fully linked-up design.

Focusing on relatively small-scale problems of large corpora helps address questions (debates, letter pathways, subnetworks) that will really help scholars approach and interrogate their data on the right scale.

Even if it is not reiterated, the format of the Design Sprint, applied to Design & Humanities, has proved once more extremely inspiring and at the same time productive.

Conclusion and further research

Knowing that the likelihood of arriving at definitive results in five days’ work is extremely small, we deliberately left some of the options open for further refinement and development. In general terms, we regard the “scatterplotish” view as an aesthetically pleasing and yet highly functional container that could be enhanced with additional information. This concerns

-

Scatterplotish (1) / direct correspondence: one could add, by way of colours, information on language or topics (cf. Como I / EMLO group) and/or scale the bars according to word count of the letters;

-

Scatterplotish (1) / direct relation: one could add data from different sources (articles and learned journals, reviews, etc.) to illustrate dimensions of the relation of two scholars beyond correspondence

-

Scatterplotish (4) / letter pathways: one could also arrange the same data in a chronological way, allowing, for example, for a view that highlights all letters (out of the total) in which the designated scholar is in a specific role (i.e. when in his life did Leibniz tend to use intermediaries?).

Regarding the overall format of Design Sprints, one can observe that there is a difference between a first event of this kind, and one (or potentially more) similar follow-up events later on. It is very useful to have at least some experienced partners on the design and the scholarly side. However this leads to a number of observations that could be useful when thinking, for example, about a “series” of design sprints:

-

the mottos for successive days could be applied in a different way - one “converges” earlier, and potentially also comes to results earlier.

-

a clear choice could be made early on regarding the difference between “prototype” and “sketchbook”.

-

a take-away product could be a one/two-page specification usable for follow-up applications.