PHILUS

Looking at the various networks of erudite correspondence exchanged between individuals in the different centers of learning of the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe.

Project leader: Guy Lazure

Scholars: Alex Butterworth, Guy Lazure, Cal Murgu, Margherita Parigini

Design researchers: Ángeles Briones, Michele Invernizzi

About the project

In modern scholarship, Renaissance Spain has been traditionally presented as marginal to the great cultural movement of the period called Humanism. One way to change this unjustified reputation and give a more accurate sense of the vibrant intellectual activity going on in the Spanish monarchy during the 16th and 17th century, is to look at the various networks of erudite correspondence exchanged between individuals in the different centers of learning of the Iberian Peninsula (cities, universities, the court) and the rest of Europe.

Letter writing has always been considered a defining attribute of Renaissance scholars, and mapping out this Spanish Republic of Letters has helped lay solid documentary foundations to this critical historiographical reassessment. The personal library collections of these scholars offers another entry point to understanding the intellectual life of Spanish humanism. The current project sets out to visualise multiple facets of the data available for these collections. Particular emphasis is given to the prohibition or disapproval of particular books at different points during the period.

Aim of the project

As a collaborative research project between humanities domain specialists and experts in interpretation and visualisation, the research question was refined during the initial discussion. The Spanish Republic team had brought a range of possible questions related to the selected data, as well as additional correspondence data. The original aim was to create a spatio-temporal representation that synthesised the two data sets to allow accessibility to a range of researchers. Whilst it was recognised that this had broad value, having explored a range of approaches the decision was made to develop an innovative tool primarily for research purposes. The Spanish Republic of Letters libraries data provides a powerful test case for the study the book collecting profile of humanists from specific territories.

-

How “open” is the Spanish Republic of Letters to Non-Catholic (Protestants, non-sanctioned) scholars/ titles?

-

How “open” is the Spanish Republic of Letters to Non-Catholic (Protestants, non-sanctioned) scholars/ titles, as viewed through humanist library collections?

-

What is the relationship between the acquisition of books by Spanish humanists, the official sanctioning of specific texts by the periodical Index of censored works, classification of subject matter, and the place of publication?

-

What do visualizations of Spanish humanists’ libraries reveal about the relation between book acquisition, collection habits, and the Index of prohibited books? What do visualizations of entire library collections and individual copies reveal about the life of books as material objects and repositories of knowledge?

Case study

The aggregated data available for the purposes of the design sprint represents a selection of library collections gather from varied published and digital catalogues. The bibliographic details contain categories including owner, author, date of publication, place of publication, date of acquisition, place of acquisition and subject. It includes approximately 1500 items comprising the libraries of eleven humanists.

Design process

The first phase of the design process was exploratory. The interdisciplinary composition of the team brought a mix of unique challenges: we had to identify the value in the diverse skills of each member, translate disciplinary specialities into palatable vernaculars that we could exchange.

During the second phase, we entertained two visualization possibilities. The first concerned the representation of humanist knowledge networks, while the other focused on representing the relationship between humanist library collection, the Renaissance book trade, and the Index of Prohibited Books. After deliberation and strong advice from supervisors the group decided on the second option.

The designers sketched a variety of possible approaches to visualize this data, exploring how different facets of the data might be linked and exposed. These concerned individual books and collectors, places of publication and their confessional affiliation, classification of subjects, dates and their presence or otherwise on indexes of prohibited books and authors. In parallel to the design process, the data was refined and additionally tagged, based on online bibliographical resources.

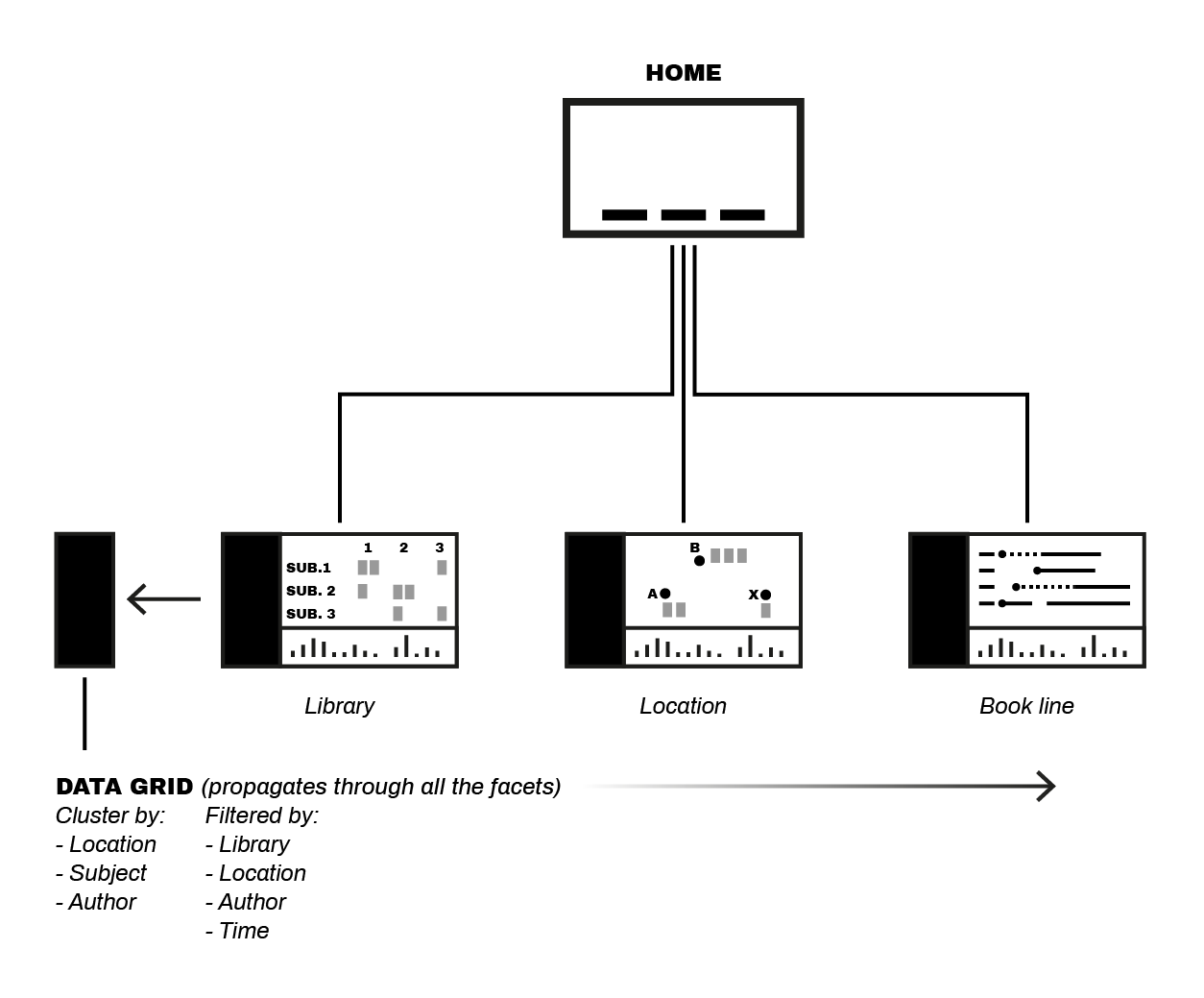

The process was iterative, leading towards an approach that represented the varied relationships between the data in a single panel, animated between different views but with a persistent focus on individual books. At the core of this was a complex timeline of multiple book ‘biographies’ (BookLine) that users can use to follow the lives of texts.

Project Diagram

Conclusions

The Bibliof-philus visualization represents the lives of the libraries of Spanish humanists (when books were published, where they are published and when they were acquired). Currently, no such tool exists that allows for research into the material lives of these objects. Bibliof-philus attempts to fill this historiographical gap.

The most interesting obstacle that we encountered centered on one fundamental question: How does one design a dynamic visualization comprised of static instants that supports a clear and fluid process of complex humanistic inquiry? A simple solution for this problem does not exist; however, we agree that to solve it designers must be welcomed into the conceptual fold from the very beginning of the process.

The visualisation offers a multi-faceted perspective on the biographies of books in the library collections of Spanish humanists. The perspectives represent the presence books in specific collections, within subject classifications, and in relation to their place of publication, filtered by time period, with a persistent indication of their approved or prohibited status according to the Inquisitional Index. An additional view represents the lifeline of books individually and in collections, indicating these factors in greater temporal detail.

The filtering and clustering is persistent across views according to the principle that individual books can be followed through different representations. Animated transitions (yet to be implemented), in which book icons move within the panel view into different semantic configurations, emphasise this feature of the tool. This allows the viewer to trace, for example, the biography of a prohibited work from its place of publication, through its inclusion in a particular library, and in relation to other books in the collection at the same time.

From the review at the end of the second phase, it became apparent that the project had potentially wider application within the study of the Respublica literaria, and even beyond it. We situate this design-led research activity in a field that encompasses the History of the Book as well as the scholarship of Early Modern Humanism and the original, specific context of the Spanish Republic of Letters.

We strongly believe that the visualisation tool we have begun to develop during the workshop has the potential to make a significant and lasting contribution to scholars working on and with early modern libraries, by helping them make clear visual sense of a large corpus of information that is still all too often presented or analysed in a purely linear and descriptive fashion. What Bibliof-philus proposes is a dynamic and interactive way to understand the early European book market through the collecting habits of those who in large part created it: scholars, erudites and bibliophiles. The possibilities to expand and enrich this tool are numerous and multi-layered. Trying to express the genealogy and itinerary of both entire collections and individual books on a visual level is a critical aspect that is worth exploring. Likewise, finding ways to connect the history of these libraries with the letters their owners wrote (in which they often referred to their books) deserves careful consideration. Lastly, incorporating digitized versions of annotated copies can also help scholars shed light on the intellectual practices of early modern collectors and members of the Republic of Letters in their attempt to produce, preserve and transmit knowledge.

This process has generated a number of questions that need to be addressed. Specifically, how could we redesign the visualization to accommodate a much greater diversity of metadata concerning the biographies of books, individually and as part of collections? For example, the acceptability of individual books according to particular criteria (listing on different indices, mentions in humanist letters, or inquisitorial trial records). Moreover, we must develop a “visual language,” or representational method, that can represent the varying status of books by additional criteria to account for questions such as how books came to be in a particular place at a particular time (initial acquisition, redistribution after the owner’s death, disappearance of books due to theft or accident)?